Read, Think, Talk, Write

A Process for Refining Information (A.K.A. How to Grok)

Advocacy is often about poring through volumes of information – much of it useless – to identify the hidden gems that could make or break a case. The system I use to wrap my mind around a complicated legal matter – or any significant interest in life – is to read about it, think about it, talk about it, and then write about it. It involves eliminating irrelevant information and forming what’s left into a cohesive idea. Call it information refining. It’s a process, and for the person going through the process, it’s an experience – the experience of understanding.

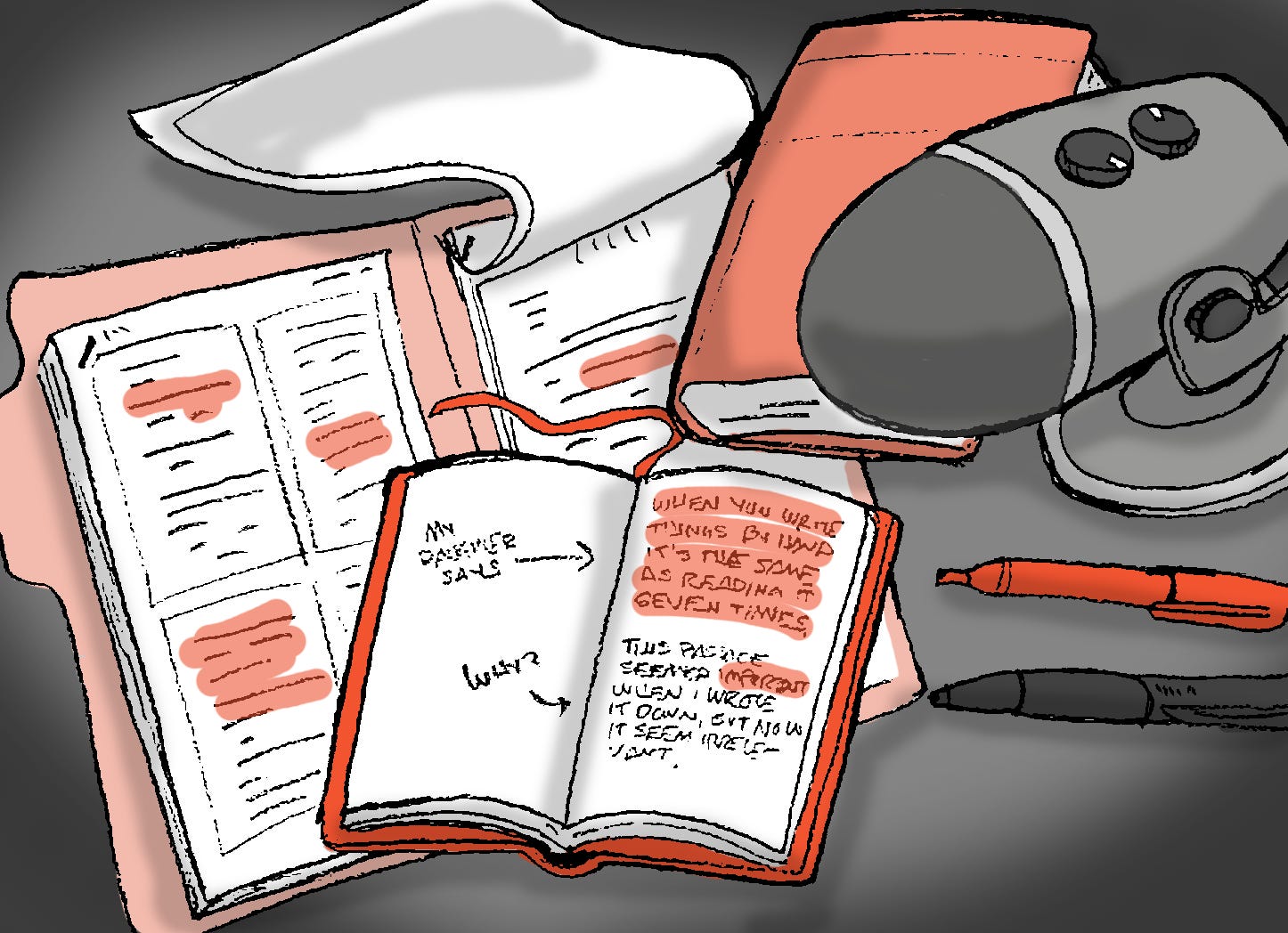

I read with a highlighter. When I encounter something remotely interesting, I cover it in orange (of course, I prefer orange highlighters). I use the highlighter liberally, and if I do it right, I might not need to re-read the entire document (handy for 400-page deposition transcripts). Later, when I review my highlights, I copy any passage I still find significant into a Moleskine notebook.

I write by hand. My daughter taught me that copying a text manually is equivalent to reading it seven times. My goal is to work solely from my notes and never have to refer to the original document, so I copy a little more than necessary. Somehow, the pain of writing out a passage by hand is eclipsed by the thought of rooting through a fat document searching for a quote that I vaguely recall reading.

As I copy the passage, I contemplate why it’s important enough to take the effort. Spending time with the words helps fix them in my brain, embedding them with context and purpose. I copy the passages into the right page of my notebook only. The left page is reserved for my thoughts. It’s where I note connections and themes as I review the passages later. Here, my highlighters may re-emerge – big ideas in orange, key terms in blue, and key people and dates in green.

Then I put the pens and paper away, and it is time to think. For me, thinking is like trying to fit puzzle pieces together. It’s about creating order from chaos and finding a structure that holds all the components together. I prefer to do my thinking during walks, over a leisurely lunch alone, or on a long drive if I’m traveling for business.

I had an associate who liked to do her thinking while swimming laps. She called it “soak time.” Another colleague of mine recommended the book “Stranger in a Strange Land,” a 1960s sci-fi classic about a boy, raised by Martians, reintegrating into human society. When he encountered a new human concept, he would curl up into a ball – sometimes while at the bottom of a pool – until he understood the concept so well that it became a part of who he was. The process is called “grokking.” To grok is to understand profoundly and intuitively.

Without the benefit of a Martian upbringing, I am unable to grok a concept simply by curling up into a ball and thinking about it. For me, it requires a little more work, so the next step is talking.

Many of the ideas that emerge from my “soak time” are soggy – soft and not fully formed. This is when it is good to have a conversation with an associate or confidant. The challenge of articulating a concept to a third party helps firm up the ideas. My conversation partner often asks questions that expose holes in my thinking. Sometimes they reveal something from their own experience that fills in some of the gaps, illuminates a new connection, or forces me to look at things from a different perspective. If the other person already has some knowledge of the subject, I can add their informed insights to my understanding. Often, a good conversation will reference a book or a relevant document, which may send me back to the reading part of the process. A good conversation challenges, reframes, and supplements my understanding of a concept, while also allowing me to practice articulating my ideas to others.

When appropriate, I like to record conversations (with the other party’s enthusiastic consent, of course). It may be an informal interview meant only for my personal use, or it may be intended for use in a podcast. Either way, I like to imagine there is an audience for the conversation, which means, as the host, I must provide context and structure to the conversation so a hypothetical audience can follow and enjoy the discussion. The transcripts of these conversations become valuable texts for me to review, which, once again, leads me back to the reading part of the process.

After I have read, thought, and talked – and reread and discussed some more – I find myself repeatedly returning to the same core concepts. Gradually, a set of conclusions begins to form. At this stage of the process, I am intimately familiar with my source material. I’ve developed a cohesive argument that has been challenged and tested by respected peers, and I have had some practice communicating my thoughts to interested third parties. Finally, I’m ready to write about it.

I find it interesting that we call the process of drafting a composition “writing.” The physical act of putting words on a page (or typing them onto a screen) is just the final step in a long process that is referred to by the deceptively simplified term “writing.” It’s as if the man who drove the spike into the rail on the last section of the Transcontinental Railroad took credit for building the whole thing, discounting the people who conceived of it; the surveyors who mapped the route; the workers who made the grade, building bridges and carving tunnels — not to mention the politicking, diplomacy, finance, and industry that made such a feat possible.

Writing may not be as difficult as building the Transcontinental Railroad, but by the time you’ve labored through all the work required to draft a cohesive composition, you reach a deep understanding of the subject matter. Whether or not anyone ever reads your manuscript, if you’ve gone through the information-refining process of reading, thinking, talking, and writing, then you have undergone a substantial experience related to your subject.

Who are we if not the product of all of our experiences? As advocates, I believe, it’s not enough to simply understand our arguments. To be compelling to the opposing counsel, a judge, or a jury, we have to become our arguments. We must believe so that others can believe. After you have gone through the process of reading, thinking, talking, and writing, that experience becomes part of who you are. It’s the closest a non-Martian can come to “grokking.”